Hefner himself plays a major role, not just in real footage over half a century, but from an extensive interview he did in 1991. Matt Whelan is convincing as a young through middle-aged Hefner, and provides narration throughout. The same formula is effectively employed for Hefner's inner circle and brain trust at Playboy - recent interviews with the real people mixed with actual footage of them in their younger days, and lots of docudrama reenactments for the earlier days - as well as for important women in the story, including Barbie Benton (described by Hefner as the "love of my life"), Dorothy Stratten (a gorgeous blonde Playmate murdered by her jealous husband), and Marilyn Cole (British Playmate who helped Playboy in its competition with Penthouse by showing some frontal nudity).

The battle between Playboy and Penthouse, which came on the scene in America (I'm not going to try and avoid double entendres) in 1969, some 16 years after Playboy launched its first issue in 1953 with Marilyn Monroe on the cover and never looked back, is indeed one of the major themes of the documentary (or its second half). This true story of escalating nudity in the competition for readership and its conclusion in the 21st century and the age of the Internet is especially relevant to media theory. Playboy's circulation today of 600,000+ is less than 10-percent of what it had at its height in the 1970s (over 7 million for its November 1972 issue), and Penthouse, which with its raunchier pictures briefly exceeded Playboy's circulation in the 1970s, now has just a little over 100,000. The reason is the instant access to porn on the Internet, which caters to every taste, and, by the way, is free.

The U. S. government, by the way, did its utmost to stamp out freedom of expression on the Internet (see my analysis in The Soft Edge of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 and the Supreme Court's wise ruling that it was in violation of the First Amendment), and though it by and large did not succeed regarding the Internet, it hounded Hefner throughout his career, and did some damage. Hefner himself was never convicted of a crime, but his casinos in New Jersey and England (the British government was no better than the American) were denied liquor licenses on pretexts, and Hefner's long-time assistant Bobbie Arnstein took her own life in the Nixonian 1970s when faced with the choice of going to jail or making up garbage about Hefner. This tragic example of a U. S. Attorney behaving like Gestapo has special and chilling relevance in our own age of Trump.

But as this documentary makes clear, Hefner and Playboy were often targets not only of the government but the media, which should have been Playboy's staunchest defenders on freedom of expression, but were either too dumb, blind, jealous, or all three to see that. In this regard, I was surprised to see what what a, well, a-hole the young Mike Wallace was in his smug sneering interview of Hefner in the early days (though a much older Wallace seems to admit the error of his younger ways).

Gloria Steinem and the feminist critique of Playboy is yet another related issue, and I'd say that both sides have merit to their positions here, so to each her/his own. Hefner to this day insists he's always been a champion of women and their rights - including medical care and control over their bodies but also taking off their clothes for Playboy. The feminist argument that this last part "objectifies" women is also true. My own view, for what it's worth, is that everything's ok among consenting adults.

There's almost no such thing as a perfect documentary on a subject you know well, because it's almost sure to leave out some things that you deem significant, inevitable given you didn't make the documentary. I regretted no mention of the Marshall McLuhan interview in the March 1969 Playboy in the otherwise good segment on the importance of the Playboy interviews, because McLuhan was not only the most important media theorist in history but that interview was by far his most informative (see my McLuhan in an Age of Social Media for why his ideas are more relevant than ever today). And, similarly, no mention of Alice Turner and the great science fiction she brought to the magazine in the 1990s (I met Alice when I was President of the Science Fiction Writers of America in 1999, so I guess I'm a little biased).

But these are small quibbles indeed about an outstanding documentary, free on Amazon Prime, which everyone interested in media and the popular culture of the past 60 years should see.

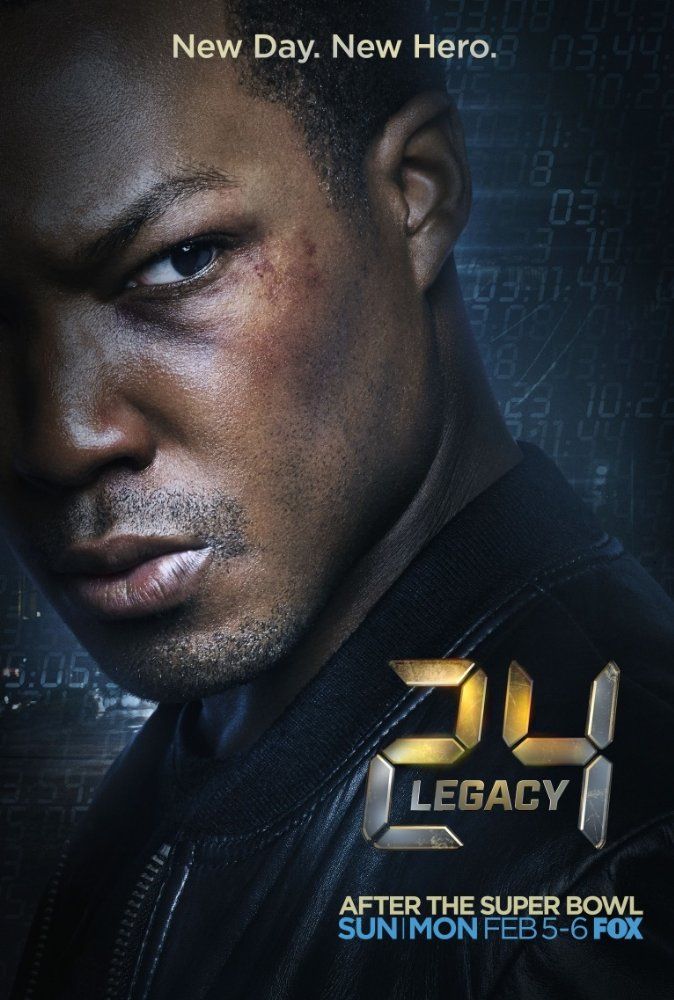

A fine - better than fine - finale to 24 Legacy's first season tonight. The series still has the punch of the original, and the power to move us with stories that make us care about the complex characters. The original series as well as Legacy have been dismissed in some places as adrenalin joy rides, but there was always more to the first, and that still holds for the second.

A fine - better than fine - finale to 24 Legacy's first season tonight. The series still has the punch of the original, and the power to move us with stories that make us care about the complex characters. The original series as well as Legacy have been dismissed in some places as adrenalin joy rides, but there was always more to the first, and that still holds for the second.