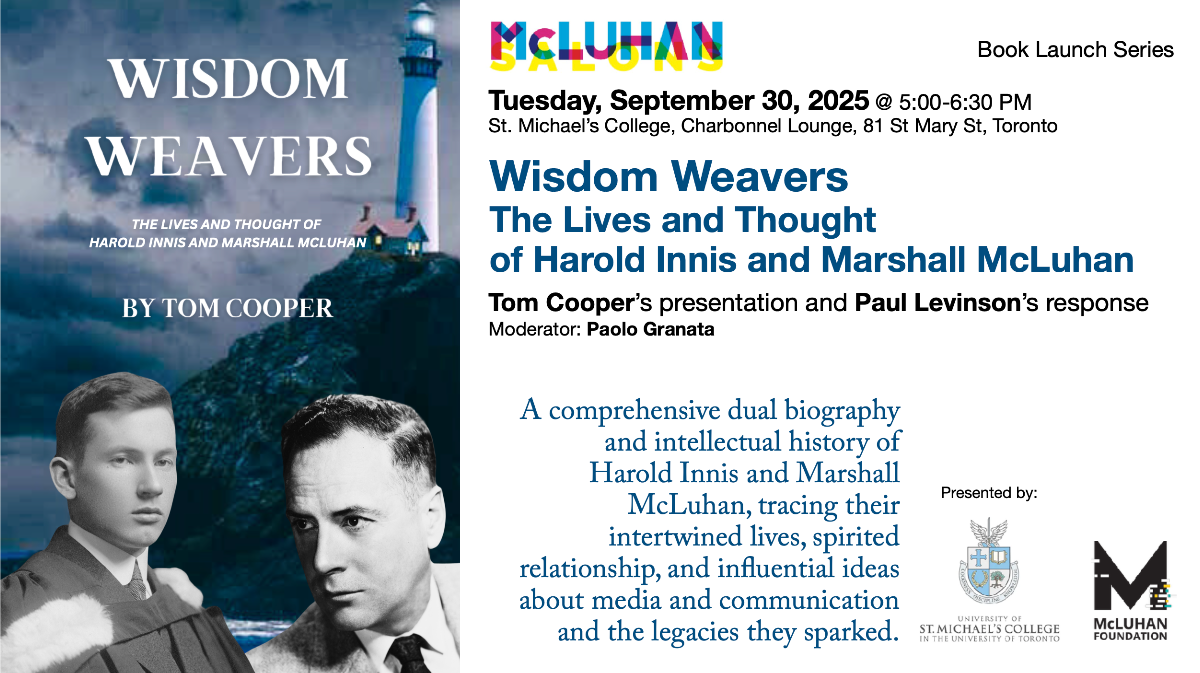

On September 30, 2025 I took part in a McLuhan Salon organized by Paolo Granata in Toronto. The Salon was devoted to a consideration of some of the many issues Tom Cooper explored in his book Wisdom Weavers: The Lives and Thought of Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan, published by Connected Editions on May 1, 2025. The following is a slightly edited transcript of my responses to each of the three sections of Tom Cooper's presentation, in addition to my responses to two subsequent questions raised by members of the audience. The audience in Toronto was present in-person with Paolo Granata at the event. Tom Cooper and I attended via Zoom.

Part 1I've been thinking increasingly in the last couple of years that the work of Marshall McLuhan and Harold Innis has never been more important to our world than it is now. As all of you up in Canada know all too well, the United States is being pulled apart by a President and his supporters, who seem to be happily marching increasingly towards a fascist government. And people who are upset and concerned about that are, among other things that they're doing, desperately struggling to understand how that happened, and what we can do, if we do understand how and why that happened, to stop and reverse that trend.

So, Tom Cooper contacted me in August of 2024 -- it seems now like about 10 years ago, because so much has happened since then -- to tell me about his book, Wisdom Weavers, an intellectual biography of Marshall McLuhan and Harold Innis, which he wanted to get published. By the way, it's worth noting that this book literally has been about half a century in the making, in the writing. And that's something that we all know, that books take a long time to write, and sometimes even longer to get published, but I think most of us can agree that 50 years is a very long time. But that's one of the great strengths of the book. And Tom had been working on this, and has been witness to all of the political upheavals in the United States.

And I have noticed, if you pay any attention at all to the news, in this struggle to understand how we got here -- we being we here in the United States, we being the United States and Canada, we being the whole world -- that increasingly, Marshall McLuhan's name comes up, because most people who understand anything about the history of communications and media, who at all have a sense that what we see and hear on television, listen to on the radio, talk about through our smartphones, and most importantly, what we do now through social media, are also aware that, well, there was this theorist Marshall McLuhan, who talked about a global village. Not in 2012, not in 2002, not in 1992, but way, way back in 1962.

And maybe some of the things that McLuhan talked about, and as we also know, when you delve into the history of Marshall McLuhan as a scholar and as a person, his awareness of and interaction with and reading the works of Harold Innis, maybe, maybe that has something that we can learn from and we can use to help us better contend with these momentous changes.

So when Tom contacted me and told me about his book, I immediately said, well, send it to me. And that very evening as I was reading it, I knew what a crucial gift this would be to our current world as we struggled to make sense of what was going on.

So I don't think that Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan have ever been as important to the world as they are now, and I think we're very fortunate to have a book like Wisdom Weavers that can tell us so much about those two.

And I'm glad that I happen to have this publishing company, Connected Editions, that could publish this book. My wife Tina Vozick and I, back in the early 1980s, created an organization called Connected Education. Connect Ed or ConnectEd, for short, and what we were doing back then was offering online courses for academic credit. And we had arrangements with the New School for Social Research, with Bath Spa University, originally called Bath College over in England, with Pacific Oaks University out on the West Coast of the United States. And we had this program going for about a good 15 years -- before I got tired of teaching online and decided to go back to the classroom and teach in-person -- but one of the things that I thought our organization could benefit from was creating an online publishing company, and since we had Connected Education, I thought it would be good to have another Connect Ed company, in this case, Connected Editions.

That's how the publisher of Wisdom Weavers was created. And when we decided to wrap up Connected Education, we still kept Connected Editions going, because we'd published a few books, and we thought they were important books. But, Connected Editions was pretty much in the closet in 2024, so in addition to everything else, the timing was right, because when Tom and I had that conversation, and, I got off the phone, and Tina said who are you talking to? I said, well, you may recall Tom Cooper. And I immediately said, you know, maybe it's time to bring Connected Editions back into the forefront, back into the fight to not only get more people aware of the important things in the world, but in the fight that I think all of us who believe in freedom are now conscripted in the political army to fight.

Part 2

I'd like to talk about about the power of parasocial relationships. And here's a true story that concerns Marshall McLuhan.

It also concerns a very good friend of mine, someone who sat next to me in the Media Ecology Program at NYU, who completed his PhD, literally, in the same few months that I completed mine. His name may be familiar to some of you, Joshua Meyrowitz. And here is this true story which shows the power of parasocial relationships, which, by the way, Josh Meyerowitz, who's remains a very close friend of mine, investigated in his doctoral dissertation, No Sense of Place, which he eventually, I guess, 6 or 7 years after he finished his PhD, developed into the book No Sense of Place, which is on the verge of celebrating its 40th publication anniversary by Oxford University Press.

Anyway, as many of you, maybe all of you, know, December 1980 was a pretty grim time as far as the loss of people that many people in the world, for different reasons, regarded as absolutely essential to their understanding of the world.

One was Marshall McLuhan, who had suffered a stroke earlier in that year, but left us, finally, in December 1980. And at that point, I was pretty close friends with Eric McLuhan, Marshall's son. And with Corinne McLuhan, Marshall's wife -- and by the way, there's a lot about the women, who played such a big role in both Marshall's life and Harold Innis' life, in Tom's book.

But as soon as we heard about Marshall's passing, Tina and I knew that we were going to go up to Toronto to attend as much of his funeral and services as people who are not members of his family could attend. And that's what we did. And as we were getting ready to do this -- that is to go up to Toronto, Tina and I -- I called Josh, who at this point was teaching at the University of New Hampshire in Durham, New Hampshire. He was then married to Candy Leonard, who would go on to actually write a couple of books about the Beatles, a very significant author. And I said to Josh, by the way, are you and Candy going to come up to Toronto for Marshall's funeral?

But another tragedy had occurred in December. John Lennon was assassinated. And, as I've been telling people for a while, ever since I wrote a novel called It's Real Life, an Alternate History of the Beatles, in which John Lennon was not assassinated, that killing changed my life. The novel is fiction, science fiction. Which I enjoyed writing. But in our world, the reality is he was assassinated.

And so those two things happened in December 1980. And the point I'm getting to is that Josh said, no, we're not going to go up to Marshall's funeral much as we would want to.

And I said to Josh, well, why not?

And he said, well, there's an event in Manhattan. People are getting together to basically express their horror at what happened to John Lennon and their love of John Lennon and his music. And Candy and I decided that's what we're going to do. We're going to be traveling, but we're going to travel from New Hampshire to Manhattan, not from New Hampshire to Toronto.

And if you think about it, there you have a parasocial relationship so powerful, that even though Joshua Meyrowitz had met McLuhan -- in fact, one of the things that I was happy that Tom picked up on in Wisdom Weavers was the pot roast dinner that Tina made the night before the Tetrad conference that I organized at Fairleigh Dickinson University in the late 1970s, a dinner in which Marshall and Eric, Tina and I, were joined by Joshua Meyerowitz and Ed Wachtell, another media theorist -- but even though Josh had broken bread with McLuhan, sat across a dinner table with him, Josh and Candy decided to go to Manhattan because of their parasocial feelings for John Lennon.

So yes, Marshall was someone that Josh felt very close to. But the power of his parasocial relationship with John Lennon led him to attend that event in New York, even though he had never met John Lennon in person. (By the way, I had met John Lennon in person once in a crowded elevator in a building in New York City.) So the parasocial is indeed an incredibly powerful force in all of our lives. We all interact with all kinds of media all the time. And we have very profound emotions about people who don't know us from Adam or Eve. And it's important to pay attention to that.

I wanted also to move to a slightly different topic to defend Marshall McLuhan and what he came up with, one of his most famous "probes," as he would call it. I would call it a concept, but it doesn't matter what the word is. But I'm talking about the "global village". And I think you have to give McLuhan enormous credit for that. In 1962, what got McLuhan to write about the global village, no doubt, was television. And if you think about it, there was nothing global about television back in 1962, and I'm old enough to remember that. And I can see, looking at the audience, that a few of you are old enough, too.

And, not only was it not global, what television created, it wasn't really a village either.

It was national in countries like the United States. Okay, that's a lot of territory, but TV did not create a village, because last time I checked, in a village, people could talk to each other, exchange ideas, across and throughout the village.

What television was ... well, it was basically a media environment of one-way wires. People watched television, but they couldn't communicate at all with the people who were on television. At most, they could communicate with people in their own families, and some friends, and maybe some business associates. At the proverbial water cooler.

So, in this environment, McLuhan talks about the global village. And the global village doesn't come into actual being until a good 30, 35 years later, when the Internet, the web, first came on the scene.

And obviously, the world we live in now is indeed a full-fledged global village, with all its benefits and all its dangers. So McLuhan may not have been entirely right about the global village, but you have to give him credit. You know, you talk about foresight, you talk about a perception that can span decades into the future. His understanding of human communication was so deep and rich that he was able to foresee -- not just predicting something, like some swami who might be able to say, I can predict the future, but no, McLuhan' notion of the global village was based on his insight into human communications, and I think that's one of his most signal accomplishments.

Last point I'll make, but very briefly, and maybe at some point in the future, at another conference, or maybe later at this event, I'll tell you more about it. Here it is: I'm not as worried about AI as many other people are. I think it's just another technology. Yes, it is going to have an enormous impact, it's going to have a good impact, it's going to have a bad impact, everything in between.

We do need to understand it better. But I'm not worried that as soon as this event is finished, there's gonna be a knock at my door, I'll open up the door, and I'll see Arnold Schwarzenegger saying, is Sarah Connor here? I'm not worried about that happening at all, at least not in our lifetimes.

Part 3

Let me pick up on what I was saying about artificial intelligence. It's done us, and is doing us, an enormous amount of good in areas like medicine, in areas like transportation, and this also relates to our health.

I'm old enough to remember, and again, I can see many people in our audience are old enough to remember, when, if you were going over a bridge or under a tunnel, you had to pay a toll. That's still the case, but there was usually some person in that toll booth, a collector, who was collecting your toll.

That person's job at least 8 hours a day, 5 days a week, was to sit there, collect tolls, and breathe in God knows how much carbon monoxide. You know, it's amazing that they lived long enough time to even get trained to be a toll collector. But, now, of course, we go over bridges, we go over tunnels, and we have an AI system keeping track of our tolls, and no one has to do that kind of job. And there are many other unhealthy jobs like that.

Yet I think it's a mistake, in many ways, to even call these systems, and AI in general, AI or artificial intelligence. I think a better word would be AS. And what I mean by that is artificial stupidity.

Because the systems are still not that bright. You know, I wrote a book, very small book, about 100 pages, called McLuhan in an Age of Social Media. I update it all the time. And I thought as I was preparing Tom's book for publication, I would get an idea of how adept an advanced AI program like ChatGPT, not the free version, but, even cheapskate that I am, I paid for a pretty sophisticated version. And so I figured I would do a test case. I would ask ChatGPT, could you prepare a name index for McLuhan in an Age of Social Media (like I might want you to do for Tom's book Wisdom Weavers).

And ChatGPT said, sure. And I uploaded the manuscript, and just a few hours later, it presented an index to me.

In which it missed about 30% of the names, and also included about 4 or 5 names that it pulled out of thin air. This is known as hallucinations in the AI field.

It did do one intelligent thing. I was talking about the billionaire who bought Twitter without mentioning Elon Musk's name, so to give the AI credit, it did put Musk's name in the index it prepared.

Anyway, I worked with that AI for about 2 weeks. It constantly promised that it was going to give me a better version.

Eventually, I said, look, enough is enough already. And I took what it gave me, went over the page by page with my own eyes, corrected the index, and now, finally, there is an index to that very short book. So, one of the reasons why I'm not too worried about AI is if it can't even do an index, a name-only index for a 100-page book. I don't see how much damage it can really do in the world.

And I know there are deep-fake videos and so on, but about that, I'll say, look, you know, we've been in that situation at least as long as since Abraham Lincoln was president. And if you take a look at another one of my books, Fake News in Real Context, you'll see a picture of Abraham Lincoln. It's actually a photograph of Abraham Lincoln. But it wasn't completely of Lincoln.

You see, the problem with Abraham Lincoln was -- he was a brave president, some people consider him America's greatest president -- but one of his problems was he didn't have very good posture. So, these photographers, these early photographers in the 1860s, took dozens of pictures of Lincoln. It was during the Civil War. They wanted to make those photos look as presidential as possible. But in every single picture, Lincoln was slouching. He didn't look comfortable.

So finally, what they did is, they came up with the brilliant idea, they lopped off Lincoln's head, and they took an older photograph of John Calhoun, an notorious Southern secessionist senator. And even though he believed in slavery, he did have one good thing about him, he had good posture.

So they took the photo of Lincoln's head and put it on top of a photo of John Calhoun's body, and that's the photograph of Lincoln that they circulated. And so Lincoln looked great.

In other words, that kind of hocus pocus of fake imagery began in the 1860s. That really is the beginning of fake news, you know, through imagery and videos, and now we have deep-fake videos. The solution to the problem is not to ban AI, or even denounce AI, it's just not to believe anything you see in a video, anything you see in a photograph. Don't believe it. You know, you just have to accept that it could be manipulated. And that pulls the fangs out deep-fake AI-manipulated videos.

And now a brief point about outer space, which Tom mentioned. Here's why I think going out into space beyond this planet is so important. A very simple, straightforward reason.

I'd like to know what the hell we're doing here. That is what we as human beings, who can go out into space, who can communicate in the way we're doing right now, Tom in Honolulu, I'm up on Cape Cod, all of you are in Toronto, are all about. What is going on here? No other species can leave this planet. We marvel at the intelligence of great apes and dolphins. But last time I checked, none of them had an Isaac Asimov, none of them had a Niels Bohr or an Albert Einstein. Or a Marshall McLuhan. The great apes may be very intelligent, and all due respect to the great apes and other intelligent animals, but they don't have hold candle to our intelligence.

And not only that, we don't really know how everything was created, right? I mean, the Big Bang Theory doesn't explain it, because what created the Big Bang? What created the materials that made the Big Bang?

And as far as religions are concerned, okay, God created everything, but what created God? God created Him or Herself?

That's a clever, logical ploy, but it doesn't really answer our questions, does it? And I think the only way we're going to get a little bit better insight on what we're doing here in this world is to get beyond this pebble. Get beyond this planet where we happen to find ourselves, and see with our own eyes what is going on out there in the universe.

Obviously, not everyone agrees with me. I'll close with what my teacher, Neil Postman, probably the best teacher I ever had, but I disagreed with, like, 95% of his views, including what Neil Postman had to say about outer space. One day, when I made the same point to him that I just made to you about the need for human beings to go out into space, Neil turned to me and he said, "But Paul, you don't understand. There's no air out there."

So, you know, that was certainly true, but obviously we could travel in ships that give us air.

Part 4: Responses to Questions

(a) I think, by and large, that the only way we can improve our lives and our situations is through technology. Not only media, which are technology, but other technologies. So, one of the ways of dealing with not enough food to feed people is to have better agricultural technology -- or even, for example through genetic engineering, and I know that's very controversial in some places, but to make crops that are more resistant to natural ills, that can thrive in harsher temperatures, etc, etc.

And I see all of the concerns about the media need to be taken into a larger perspective of we're still a long way, as a species, from leading the lives we want to live. We, all of us, have disappointments that we see all around us, things which are not working well, and as I said, I can't think of any solution better than technologies which have extended our lives, have made parts of the world more conducive to human beings living there, and a whole series of other positive developments.

(b) Let me just say, I was already, before Trump became what he is today -- going back, actually,to the 1970s -- I was always very interested in the study of propaganda. How it's created and what it does. I studied it as a student in the Media Ecology program. It actually wasn't Neil Postman's specialty, it was Terry Moran's, somebody else in the NYU Media Ecology faculty, who doesn't get enough credit for his contribution to the program. And because of Terry Moran, I read the Institute for Propaganda Analysis, what that group did in their studies, which began in the late 1930s, continued into the early 1940s. And through that, and other research that I did, I became very well aware of what Joseph Goebbels and Adolf Hitler and his cronies did in Germany in the 1920s and 30s, and I became aware very early on that Joseph Goebbels was no dummy. It was Dr. Goebbels. The man had a PhD. He was a monster on an ethical basis, but he was highly intelligent, and he also understood human communication.

And the reason why I'm saying all this is it frightens me, and frighten is almost too weak a word, to see what's going on in the United States today, and in other parts of the world. Because, in many ways, it is following the exact same path that Hitler and Goebbels and their cronies followed in the Weimar Republic in the early 1930s, attacking comedians, rounding up immigrants and demonizing them. I mean, I could talk for an hour about all the things that are going on today in the United States, such as wanting to annex other neighboring countries. You know, one of the first things Trump said, after he was re-elected this second time, is, hey, he thinks Canada should become another state in the United States. I mean, this is, you know, like Hitler's Germany wanting to annex Austria, which he did, wanting to annex half of Czechoslovakia, which he did. And that finally led to World War II.

And so, this is a very real situation. And my best advice is, every single one of us needs to do whatever we can to stop that and fight that. I'm a professor, so fortunately, I have classrooms in which I can talk to my students about that. I have a blog in which I can write my head off about it. I have podcasts in which I can talk about it, I can talk about it even now to you, but every one of us who is concerned about this, well, the worst thing we can do is to keep quiet about it. We have to constantly oppose it and encourage other people to oppose it, and that was the mistake that people in Germany, well-meaning people in the 1930s, did. They didn't take Hitler seriously enough. They dismissed him as a clown. And all too often, I hear people dismiss Trump as a clown. Yes, he is, but he's far more dangerous than a clown, just as Hitler was.

in Kindle, paperback, and hardcover

No comments:

Post a Comment