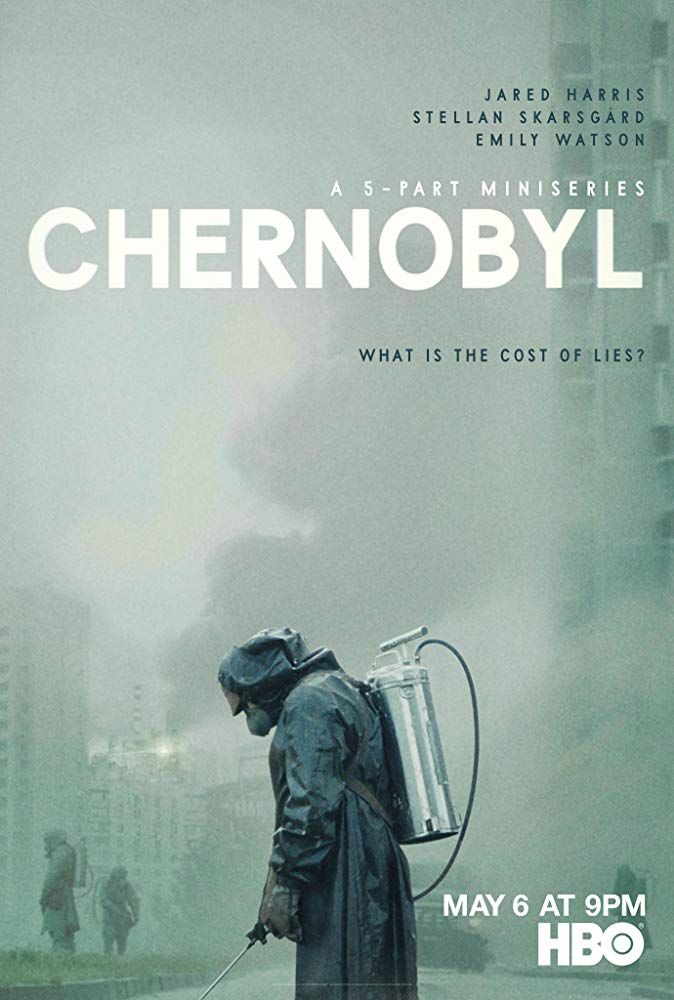

If I hadn't seen last week's first episode of Chernobyl, and had fallen asleep before the beginning of the second episode on HBO last night, and had woken up a few minutes into the episode, I'd have thought that I was watching a horror movie, or maybe a new apocalyptic series on AMC.

The second episode had all of the trimmings. Almost all the powers-that-be misunderstanding and downplaying the grave threat. A scientist or two, here and there, getting what was happening, urgently trying to alert everyone around them to the danger, being largely ignored. And when they're finally listened to, at least some of the vulnerable populace is evacuated, but not everyone, including a dog running in vain after a departing bus. And with a far worse, more monstrous catastrophe about to happen, three brave souls stepping up.

Except all of this really happened. And it could happen again, since understanding one accident can never preclude another happening, for slightly different reasons. I'm usually a champion of technology. But I turned against nuclear power after Three Mile Island in 1979 near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. That was a partial meltdown. And I wasn't surprised when the far worse accident happened at Chernobyl in 1986.

This mini-series is a stark reminder that we have take nature and our technologies which seek to harness it very seriously. Because the truth is there is no complete harnessing of the natural world - not of atoms, not of genes, not of bacteria, not of you name it. The best we can be is, yes, bold with technology in trying to improve out lot, but always wary of its unforeseen consequences.

See also: Chernobyl 1.1: The Errors of Arrogance

2 comments:

I was 13 when Chernobyl happened, i.e. old enough to understand that something horrible had just happened, but not old enough to know what exactly the danger was. And Germany got its share of fallout, though less in the North where I lived than in the South and East. I remember not being allowed to go out in the rain during recess at school. I also remember footage of milk being poured away and lettuces being plowed under, which bothered me, because we'd been taught that throwing away food was wasteful and bad. Later, friends from Latvia, then still part of the Soviet Union and heavily affected by fall-out, told me that in the Soviet Union there had been absolutely no warnings to the population outside the immediately affected areas (and not even there properly).

There already was a strong anti-nuclear power sentiment in West Germany at the time and it grew even stronger after Chernobyl happened. Construction of new nuclear power stations was stopped, but it still took until the Fukushima Daiichi disaster for Germany to get out of nuclear power altogether. And there are still nuclear reactors operating in Germany, until 2023, when the last one will be shut down.

I haven't seen the Chernobyl series yet and I don't know if I have the stomach for it. Though it's important that they made the series, because just as movies like "The Day After" and "Threads" got politicians to rethink nuclear weapons, maybe "Chernobyl" will get them to rethink nuclear power. I also keep shaking my head at reviewers who complain that the series is confusing and illogical and why do they need the subplot about the firefighter and his pregnant wife, because all that really happened. I've seen the real wife of the firefighter interviewed on German TV and her story is heartbreaking.

Power comment, Cora - thank you. Germany is far wiser than the United States in at least starting to end all nuclear production after Fukushima, with the last one to close in 2023. I wish the US would do the same.

Post a Comment